Description

Una de las mayores herencias culturales de Bolivia son los textiles andinos, cuya existencia se remonta al pasado prehispánico y ha permanecido hasta hoy como una referencia de la diversidad cultural boliviana. Los textiles andinos representan siglos de conocimientos, habilidades y destrezas técnicas que las comunidades indígenas (urus, aymaras y quechuas) ponen en práctica para elaborar tejidos de gran calidad y complejidad artesanal.

El proceso de elaboración de textiles andinos implica una serie de etapas que pueden resumirse de la siguiente manera:

Primero está la obtención de la materia prima y su preparación. Se utilizan principalmente fibras obtenidas de animales como la llama, alpaca o vicuña; también de la oveja traída por los españoles. El primer paso es la esquila de la lana que hay que limpiarla de residuos para posteriormente proceder al hilado. El hilado se hace con empleo de una rueca o huso, donde se van enrollando las fibras formando hilos de diferente grosor y torsión, dependiendo del tipo de prendas que quieran tejer. Después se recoge el hilo de la rueca y se envuelve en ovillos. Finalmente, se procede al madejado, envolviendo el hilo entre el codo y la mano.

Cuando están listas las madejas (cada una de 200gr aproximadamente), se realiza el teñido. Los textiles andinos se caracterizan por una amplia gama de colores que se obtienen a través de tintes naturales o artificiales. Los tintes naturales son el resultado del procesamiento de una serie de plantas locales que dan diferentes colores: negro/t’ara, rojo/aliso, azul/papas negras, amarillo/ch’illka, morado/maíz negro, verde/ch’illka, molle); los tintes artificiales se obtienen con empleo de anilinas importadas. Para que los colores sean uniformes y durables, es necesario hacer cocer la lana y emplear mordientes o sustancias para fijar el color: vegetales ácidos, orines, ceniza, barro fermentado, alumbre, sulfato de cobre o aluminio, sales, etc. Los tintes vegetales se obtienen por cocción.

Luego viene la etapa del tejido, cuya estructura comprende el entrecruzamiento de dos series de hilos: una longitudinal que se llama “urdimbre” y otra horizontal que se llama “trama”. Para el tejido se utilizan diferentes tipos de telares: telar horizontal o de suelo, telar inclinado apoyado a la pared, telar de cintura y el telar de pedal introducido por los españoles. Primero, se forma la urdimbre, colocando hilos entre dos barras de madera, de manera continua y longitudinal; los hilos de urdimbre deben estar separados de manera ordenada por medio de varillas o lisos de madera, de manera que formen una abertura o calada por donde deberá pasar la trama. El hilo de trama se envuelve en una naveta o lanzadora de madera, para ayudar a pasar horizontalmente la trama a través de la calada de la urdimbre. En cada pasada, la tejedora debe ir ciñendo los hilos muy bien para tener un tejido consistente, para esto utiliza un hueso afilado (femur de llama) llamado wichuña, cuando la trama está cerca de su cuerpo; cuando está más alejada, emplea un palo para ceñir. En un tejido terminado la parte llana se llama pampa y la parte decorada con diseños se llama pallay, existen tejidos completamente decorados que se llaman pallados.

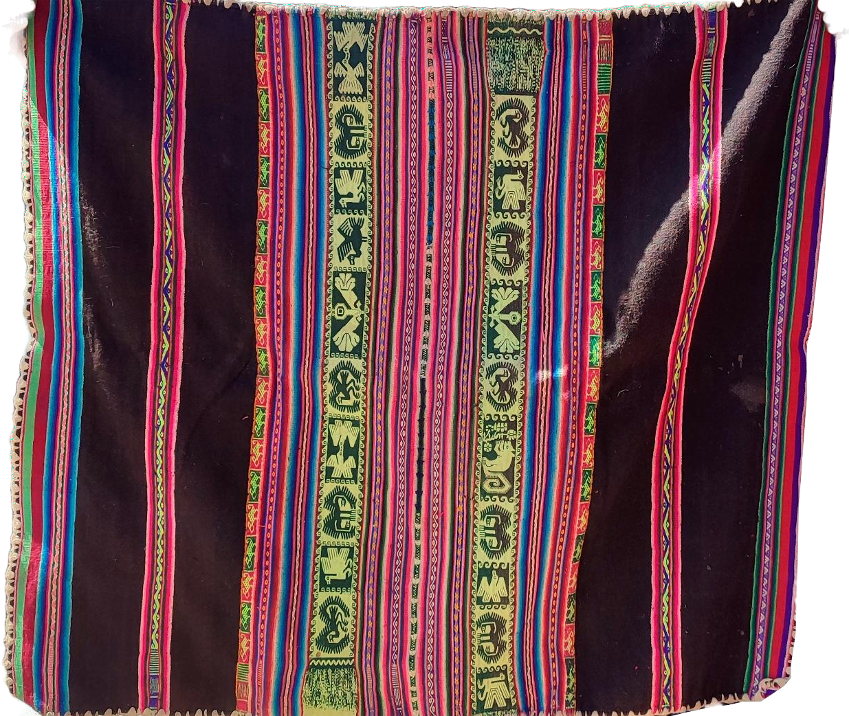

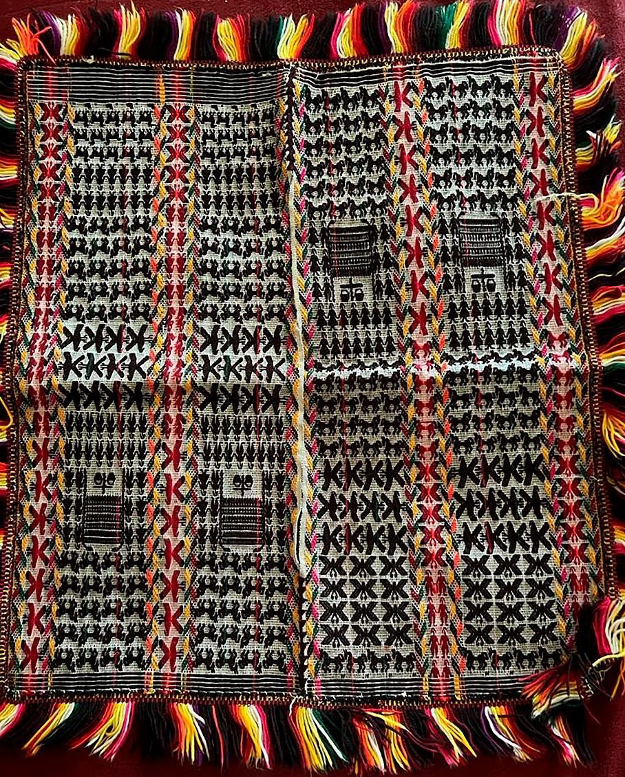

Las técnicas que se emplean en el tejido son varias y complejas, entre ellas están: el tejido balanceado con urdimbre y trama visibles, el tejido llano con trama vista, tejido llano con urdimbre vista, etc. De igual manera, los diseños o figuras dentro del tejido encierran mucha complejidad en formas, colores y significados; el conjunto de diseños se divide en dos grandes grupos: 1) Figurativos: imágenes míticas, representación de hombres, animales, plantas; 2) Geométricos: cuadrados, rombos, triángulos, zigzags, etc. Finalmente, existe una variedad de tejidos dependiendo de su uso: phullus (frazada), ponchos, costales, ch’uspas (bolsas de distintos tamaños), axsu (especie de falda de mujer), llijlla (especie de manta de mujer), cinturones, etc.

Dependiendo de las diferentes regiones andinas de Bolivia, existen diversos estilos de textiles, entre los que destacan: Tarabuco, Jalq’a, Charazani, Norte Potosí, Tapakari, Uru Chipaya, etc. La variedad, complejidad y antigüedad es tal, que varios investigadores le dedican tiempo para sus estudios antropológicos, arqueológicos, estéticos, lingüísticos y otros aspectos reflejados en la producción de textiles andinos de Bolivia; por su parte, las comunidades andinas continúan con esta práctica artesanal ancestral, aunque en menor medida debido a la invasión de textiles y ropa industrial en los mercados.

english

Andean textiles

One of the greatest cultural heritages of Bolivia is the textiles whose existence dates back to the pre-Hispanic past and has remained until today as a reference of cultural diversity. Andean textiles represent centuries of knowledge, skills and technical abilities that the indigenous communities (Urus, Aymara and Quechua) put into practice to produce textiles of great quality and artisanal complexity.

The process of making Andean textiles involves a series of stages that can be summarised as follows:

First, there is the obtaining of the raw material and its preparation. Fibres obtained from animals such as the llama, alpaca or vicuña are mainly used, as well as from sheep, brought by the Spaniards. The first step is the shearing of the wool for spinning. The spinning is done using a distaff or spindle, where the fibres are wound into threads of different thicknesses and twists, depending on the type of garment to be woven. The yarn is then collected from the spinning wheel and wrapped into balls. Finally, the skeins are made, wrapping the yarn between the elbow and the hand.

When the skeins are ready, dyeing takes place. These are characterised by a wide range of colours obtained through natural or artificial dyes. The natural dyes come from a series of local plants that give different colours: black/t’ara, red/alder, blue/black potatoes, yellow/ch’illka, purple/black corn, green/ch’illka, molle); the artificial dyes are obtained by using imported anilines. In order for the colours to be uniform and durable, it is necessary to boil the wool to fix the colour: vegetable acids, urine, ash, fermented mud, alum, copper or aluminium sulphate, salts, etc. Vegetable dyes are obtained by boiling. Different types of looms are used for weaving: horizontal or floor loom, inclined loom leaning against the wall, backstrap loom and the pedal loom introduced by the Spaniards. First, the warp is formed by placing threads between two wooden bars, in a continuous and longitudinal manner; the warp threads must be separated in an orderly manner by means of rods or wooden slats, so that they form an opening or fretwork through which the weft must pass. The weft thread is wrapped around a wooden shuttle to help the weft pass horizontally through the warp shed.

On each pass, the weaver must weave the threads very tightly in order to have a consistent weave, using a sharpened bone (llama femur) called a “wichuña”, when the weft is close to her body; when it is further away, she uses a stick to weave. In a finished weave, the plain part is called pampa and the part decorated with designs is called pallay, there are completely decorated weavings that are called pallados. The set of designs is divided into two large groups: 1) Figurative: mythical images, representation of men, animals, plants; 2) Geometric: squares, rhombuses, triangles, zigzags, etc. Finally, there is a variety of weavings depending on their use: phullus (blanket), ponchos, costales, ch’uspas (bags of different sizes), axsu (a kind of woman’s skirt), llijlla (a kind of woman’s blanket), belts, etc.

Depending on the different regions, there are different styles, among which the following stand out: ‘Tarabuco’, ‘Jalq’a’, ‘Charazani’, ‘Norte Potosí’, ‘Tapakari’, ‘Uru Chipaya’, etc. The variety, complexity and antiquity are great and there is research into anthropological, archaeological, aesthetic and linguistic issues. The Andean communities continue with this ancestral craft practice, although to a lesser extent due to the invasion of industrial textiles and clothing in the markets.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.